Germany has the largest economy in modern Europe. In the past, the coal industry used to play an important role; coal had been mined in the country for about two hundred years. Even now, German coal reserves are so large that they could meet national economy demands for many years to come. The main areas of coal mining are located in the main industrial centers of Germany – the Ruhr district and the Saar region. Brown coal is mined in three areas: in the Rhineland, Lausitz, and in the central part of Germany.

Previously, open-pit mining was the dominant method. Over time, the extraction of coal went deeper into the ground, became more costly, and, as a result, was no longer economically profitable. As the coal industry in Germany is subsidized, the government decided to cut funding and completely stop coal mining operations by 2018. Termination of brown coal mining is planned for 2050.

We visited Lausitz, the second largest brown coal mining region in Germany, to personally meet with former coal mine workers and ask them about how it was before and is now. Almost in the center of Lausitz, on the border between the Brandenburg and Saxony regions, lies the town of Hoyerswerda. There, we met with Jan Masnica and Frank Hirche. Today, they are retired from mining and engineering, but in previous years and decades each has made an important contribution to the local coal industry development in Lausitz.

Jan Masnica. Born in Poland in the city of Gliwice in 1951, he was trained to be a coal miner. In 1974 he moved to the city of Hoyerswerda. A few years later he retrained as a mining engineer. He worked in many mines around Hoyerswerda. After the unification of Germany, he joined the field of landscape recultivation and restoration. In 2016 he retired.

Frank Hirche. Born in 1961 in Hoyerswerda. From 1981 to 2005, he worked as an electrician in construction and coal mining. In 1993, he became a member of the Christian Democratic Union. He is currently the chairman of this party in the city of Hoyerswerda.

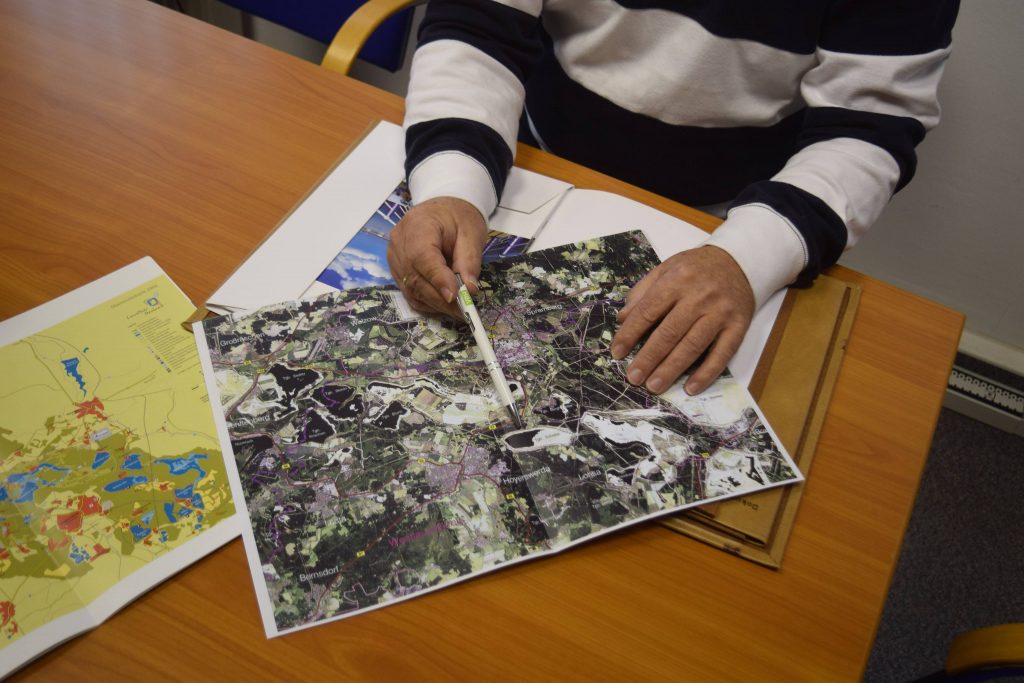

Mr. Masnica picked up the map of Lausitz: “I worked in several quarries, but the longest in Schwartz Pumpe. That was a world-class open-pit mine; approximately 310 million tons of coal was mined there per year. There’s nothing like it in the world to compare with, although, it was all achieved at the expense of damaging the earth. If you look closely at the map, you will notice dark spots – areas where landscape was destroyed. The issue of environmental damage, however, was not raised at that time.”

What is the main difference in how state agencies treated mine workers back in your days and nowadays? People usually lived in cities around coal mines in which they worked, for example, in Hoyerswerda. The government took care of those who labored in the mines. Today, it is not the case. Back in the GDR days, if you came here as a miner, there would be high chances of finding a job easily, earning well, getting an apartment quickly, and also reaping benefits. Today, it is not the case. Salaries remained high, but the overall range of social services disappeared. There is no incentive to connect your life with this occupation anymore.

What can you say about training for mining specialties? Around Hoyerswerda there were several colleges where they trained specialists in car maintenance for quarries. I myself have received several qualifications, starting as a mechanic in the mine.

Today, the majority of engineering and mining professions are not available for training; however, there are more and more opportunities for obtaining qualifications in the field of coal mining reclamation. Coal will be mined for a maximum of another 20-30 years, which is equivalent to one generation time. Therefore, recultivation of landscapes has become one of the leading areas in educational institutions that used to train workers for the maintenance of mines.

Mr. Hirche, this question is for you. In your opinion, what is the future of the coal industry? Coal mining in Lausitz had two sides of the coin. On the one hand, it was abundance of well-paid jobs, on the other – destruction of environment. The number of jobs is constantly decreasing, while discussions about environmental destruction are growing. Everything comes to a logical end. Therefore, brown coal has no future.

Regarding nature and pollution, has anyone raised such concerns in the 70-80s? Back then nobody was concerned about these issues, either in the East or West Germany. It was clear to everyone that if there was a plan to create a coal mine, then the next two villages must disappear. And you know, people took it for granted, there were no long discussions. But, of course, people had a hard time leaving their homes. Today, at least, you can complain, protest. Previously, this was unacceptable.

Regarding nature and pollution, has anyone raised such concerns in the 70-80s? Back then nobody was concerned about these issues, either in the East or West Germany. It was clear to everyone that if there was a plan to create a coal mine, then the next two villages must disappear. And you know, people took it for granted, there were no long discussions. But, of course, people had a hard time leaving their homes. Today, at least, you can complain, protest. Previously, this was unacceptable.

Mr. Masnica, what is the value of miner’s profession? There is a collective custom between miners – to be always together. This manifests itself both in the literal sense during work and in everyday life. State policy cannot influence this.

Today in the German environmental discourse there are often questions raised about climate change and coal burning. Were these questions relevant when you worked in this field? No, these questions did not exist on the agenda at all. When in the mid-2000s they approached the issue of ecology, nothing changed in the mind of an ordinary coal mine worker. Personally, I was glad that I still have a job. Today I will say that such questions were raised not in vain. Everyone needs rest and change in direction of development.

Authors: Victoria Slobodchikova and Roman Boichuk